The British Black Arts Movement and Wolverhampton: History, Impact, Legacy

Context & Origins

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the UK was experiencing heightened racial tensions. Anti-immigrant sentiment, rise of the far right (e.g. the National Front), and social inequalities shaped daily life for many Black Britons.

Wolverhampton—part of the industrial Midlands—was also undergoing economic decline and social challenges. For Black students and artists, the sense of marginalisation was urgent.

Against that backdrop, young Black British artists began to organise and produce work that explicitly addressed race, identity, inequality, politics, and representation.

The Blk Art Group (Wolverhampton-based roots)

Formation: The Blk Art Group was founded around 1979, essentially by students and young artists based in Wolverhampton and the wider West Midlands. Key founders include Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper, Marlene Smith, Donald Rodney, and Claudette Johnson.

Early Work & Exhibitions:

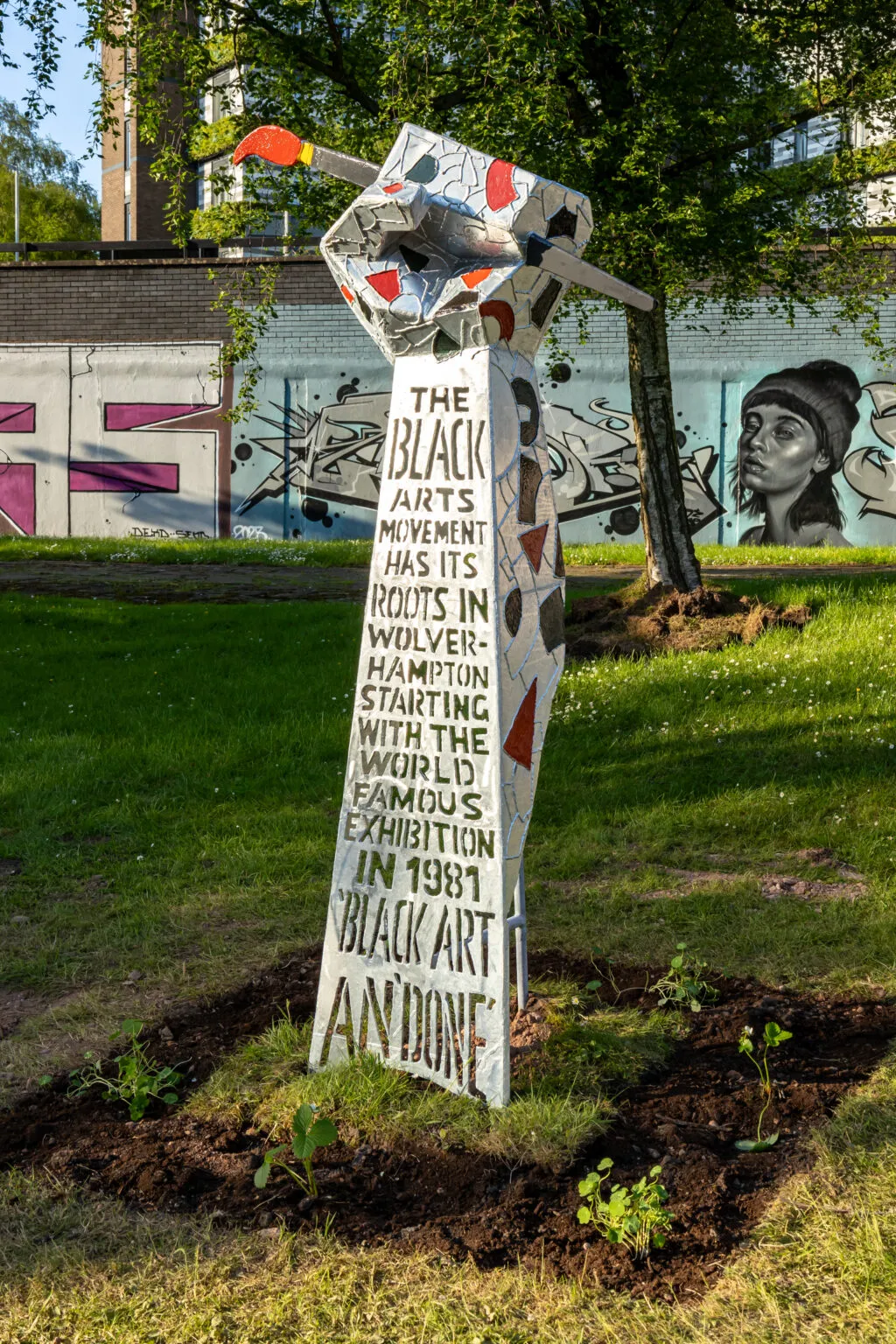

The exhibition Black Art An’ Done (1981) at Wolverhampton Art Gallery was one of the first major group shows. It gave voice to Black artists’ perspectives on racism, identity, and social issues.

Following that, the First National Black Art Convention in 1982, held at what was then Wolverhampton Polytechnic, provided space for dialogues around the form, purpose, and future of Black art in Britain.

Philosophy & Style: The Blk Art Group combined political urgency with artistic experimentation. Their work drew on multiple sources—Pan-African ideas, anti-racist activism, critique of British institutions, personal narratives. Artistically, they used mixed media, collage, found objects, installation, figurative drawing, etc. The art was often direct, confrontational, layered in meaning.

Key Artists

Some of the central figures include:

Eddie Chambers: organiser, critic, curator. Important in shaping the collective activism of the group. Work often addressed political issues and institutional critique.

Keith Piper: deeply involved in pushing aesthetic boundaries, integrating text, found materials, symbolic imagery.

Marlene Smith: one of the younger members; her work and perspective contributes to the “sense of urgency” and group identity.

Donald Rodney: powerful artist whose work often drew on personal struggle (he had sickle cell anaemia) and explored themes of the body, mortality, visibility.

Claudette Johnson: known for her figurative work, especially portraits of Black women. Her art emphasises dignity, identity, presence.

Major Exhibitions & Institutional Engagement

Black Art An’ Done (1981, Wolverhampton) — early foundational exhibition.

The First National Black Art Convention (1982, Wolverhampton Polytechnic) — helped formalise “Black Art” in Britain as a coherent movement and network.

The Pan-Afrikan Connection — a touring show; also helped spread the message beyond Wolverhampton.

Later, The Other Story exhibition (1989–90, Hayward Gallery, London; toured to Wolverhampton Art Gallery among other venues) was a landmark showcasing African, Caribbean, Asian artists in post-war Britain, partly building on what the Blk Art Group had raised.

Impact & Legacy

The Blk Art Group was relatively short-lived (dissolving mid-1980s), but its impact has been large.

It pushed the art world to recognise Black British identity and produce art around experiences of racism, migration, diaspora, identity politics. It helped establish new institutions, networks, discourse. Within Wolverhampton, its legacy is preserved and celebrated:

Wolverhampton Art Gallery’s Collecting Cultures: Black Art Project (2015-17) — acquiring works from key Black British contemporary artists, particularly those associated with the 1980s Black Arts Movement.

wolverhamptonart.org.uk

Exhibitions like Black Art in Focus (2016) showcased works by artists such as Keith Piper, Donald Rodney, Claudette Johnson, Tam Joseph, Chila Kumari Burman among others.

Influenced later generations of Black British artists. Artists such as Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce, Chris Ofili etc. have cited this movement as precedent or influence.

Challenges and Criticisms

Reception was mixed; sometimes the work was misunderstood, dismissed or marginalized by mainstream art critics and institutions. The political nature of the work, its urgency, sometimes made it uncomfortable or controversial.

Issues of gender and representation within the movement (i.e. Black women artists) have been both raised and partly addressed, but not without tensions.

Wolverhampton’s Role: A Local Hotbed, National Stage

Wolverhampton was more than just a birthplace; it was a site where Black British art was first seen, contested, debated. The city’s Polytechnic (now part of University of Wolverhampton) and its Art School played a crucial part in nurturing the early group.

The local gallery (Wolverhampton Art Gallery) served as an important early venue and continues to hold collections and exhibitions connected to the movement.

Continuing Relevance & Memory

The movement is now much more recognised in British art history than it was in its early days. Its work is being revisited, researched, and its contributions better understood.

Oral history projects (for example via Wolverhampton Art Gallery) have sought to record the voices and stories of those involved.

wolverhamptonart.org.uk

The question of preserving physical spaces associated with the movement has also arisen. For instance, the “George Wallis” building (the Wolverhampton School of Art building) is argued to have historical cultural significance because of events such as the First National Black Art Convention held there.

Conclusion

The Black Arts Movement in Britain—and especially as it germinated in Wolverhampton via the Blk Art Group—was a critical moment in cultural history. It shaped how Black British artists saw themselves and how they demanded to be seen by others. Though often born out of struggle, the movement produced work of great artistic strength, creativity, and relevance. Wolverhampton remains a key place in that story… both as a birthplace and as a keeper of the memory.